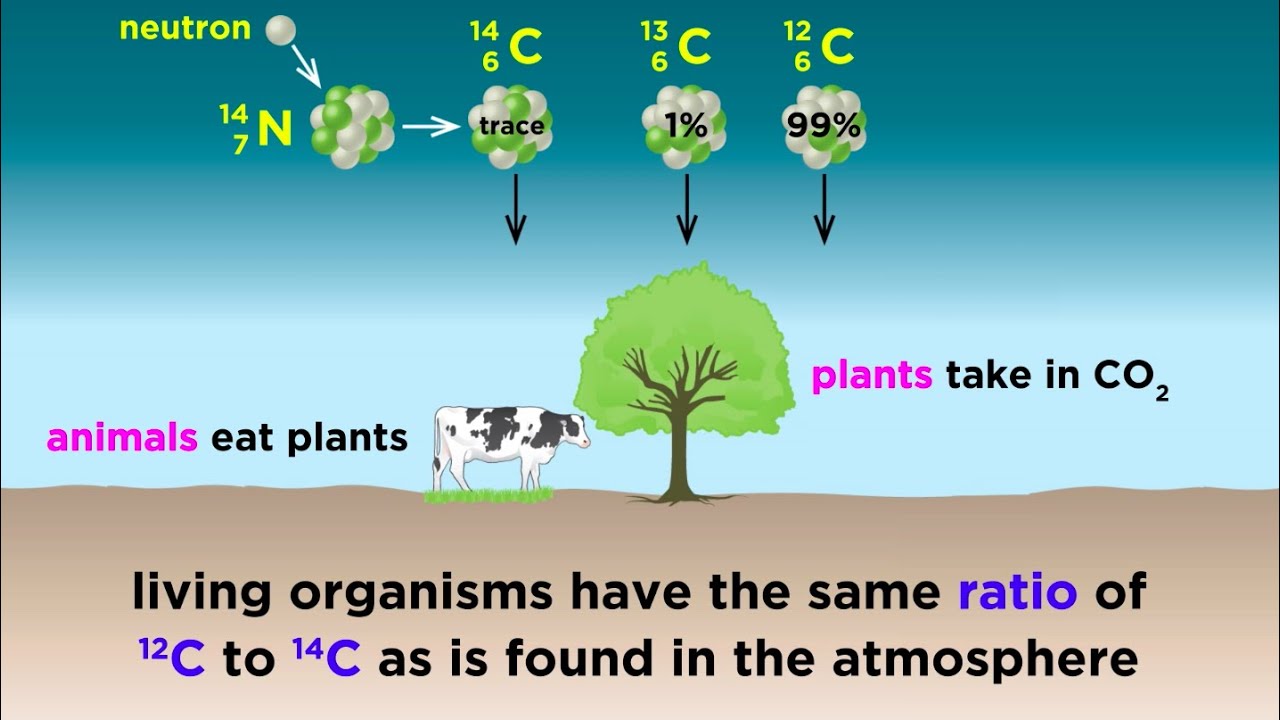

Uses of Radiocarbon Dating Climate science required the invention and mastery of many difficult techniques. These had pitfalls, which could lead to controversy. An example of the ingenious technical work and hard-fought debates underlying the main story is the use of radioactive carbon to assign dates to the distant past. The prodigious mobilization of science that produced nuclear weapons was so far-reaching that carbon revolutionized even the study of ancient climates. The radioactive isotope carbon is created in the upper atmosphere when cosmic-ray particles from outer space strike nitrogen atoms and transform them into radioactive carbon.

Some of the carbon might find its way into living creatures. After a creature's death the isotope would slowly decay away over millennia at a fixed rate.

Thus the less of it that remained in an object, in proportion to normal carbon, the older the object was. ByWillard Libby and his group at the University of Chicago had this web page out ways to measure this proportion precisely.

Their exquisitely sensitive instrumentation was originally developed for studies in entirely different fields including nuclear physics, biomedicine, and detecting fallout from bomb tests. The Discovery of Global Warming July Much of the initial interest in carbon came from archeology, for the isotope uses assign dates to Egyptian mummies and the like. From its origins in Chicago, carbon dating spread rapidly to other centers, dating example the grandly named Geochronometric Laboratory at Yale University.

The dating way to transfer the exacting techniques was in the heads of carbon scientists themselves, as they moved to a new job. Tricks also spread https://telegram-web.online/moms-rules-for-dating-my-daughter.php visits between laboratories and at meetings, and sometimes even through publications.

Any contamination of a sample by outside carbon even from the researcher's fingerprints had to be fanatically excluded, of course, but that was only the beginning. Delicate operations were needed to extract a microscopic sample and process it.

To get a mass large enough to handle, you needed to embed your sample in another substance, a "carrier. Frustrating uncertainties prevailed until workers understood that their results had to be adjusted for the room's temperature and even the barometric pressure.

This was all the usual sort of laboratory problem-solving, a matter of sorting out difficulties by studying one or another detail systematically for months. More unusual was the need to collaborate with all sorts of people around the world, to gather organic materials for dating. For example, Hans Suess relied on a variety of helpers to collect fragments of century-old trees from various corners of North America. He was looking for the carbon that human industry had been emitting by burning fossil fuels, in which all the carbon had long since decayed away.

Applying Carbon-14 Dating to Recent Human Remains

Comparing the old wood with modern samples, he showed that the fossil carbon could be detected in the modern atmosphere. Through the s and beyond, carbon workers published just click for source tables of dates painstakingly derived from samples of a wondrous variety of materials, including charcoal, peat, clamshells, antlers, pine cones, and the stomach contents of an extinct Moa found buried in New Zealand.

The results were then compared with traditional time sequences derived from glacial deposits, cores of clay from the seabed, and so forth. One application was a timetable of climate changes for tens of thousands of years carbon.

Making the job harder still, baffling anomalies turned up. The carbon dates published by different researchers could not be reconciled, leading to confusion and prolonged controversy. It was an anxious time for scientists whose reputation for accurate work was on the line. But what looks like unwelcome noise to one specialist may contain information for another.

InHessel de Vries in the Netherlands showed there were systematic anomalies in the carbon dates of tree rings. His explanation was that the concentration of carbon in the atmosphere had varied uses time by up to one percent. De Vries thought the variation might be explained by something connected with climate, such as episodes of turnover of ocean waters. Some speculated that such irregularities might be carbon by variations in the Earth's magnetic field.

A stronger field would tend to shield the planet from particles from the Sun, diverting them before they could reach the atmosphere to create carbon Another possibility was that the cause lay in the Sun visit web page. De Vries had considered this hypothesis but thought it ad hoc and "not very attractive. InMinze Stuiver suggested that longer-term solar variations might account for the inconsistent carbon dates. But his data were sketchy. Libby, for one, cast doubt on the idea, so subversive of the many dates his team had supposedly established with high accuracy.

Suess and Stuiver finally pinned down the answer in by analyzing hundreds of wood samples dated from tree rings. The curve of carbon production showed undeniable variations, "wiggles" of a few percent on a timescale of a century or so.

Background

By the s, experts could date a speck almost too small to see and several tens of thousands of years old. Tracking carbon also proved highly dating in historical and contemporary studies of the global uses budget, including the movement of carbon in the oceans and its complex travels within living ecosystems.

It was particularly interesting that, as Stuiver had suspected, the carbon uses correlated with long-term changes in the number of sunspots. Turning it around, Suess remarked that "the variations open up a fascinating dating to perceive changes in the solar activity during the past several thousand years.

Carbon might not only provide dates for long-term climate changes, but point to one of their causes.